Which Of The Following Services Must A State Offer In Order To Receive Federal Matching Funds?

Medicaid represents $1 out of every $half-dozen spent on health care in the US and is the major source of financing for states to provide coverage to run into the wellness and long-term needs of their depression-income residents. The Medicaid plan is jointly funded by states and the federal government. There has been renewed interest in how Medicaid is financed in low-cal of the additional federal financing for the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Human activity (ACA) besides as ongoing budget discussions at the federal level. This brief reviews how the Medicaid programme is financed likewise every bit the implications for budgets, responsiveness to state policy choices and demand, the links between Medicaid spending and state economies. Key conclusions include:

How Medicaid is financed

- Federal Medical Help Pct (FMAP). The federal government guarantees matching funds to states for qualifying Medicaid expenditures; states are guaranteed at to the lowest degree $1 in federal funds for every $1 in state spending on the program. This open-ended financing structure allows federal funds to flow to states based on actual costs and needs as economic circumstances alter.

- Enhanced Matching Rates. In some instances, Medicaid provides a college matching rate for select services or populations, the most notable being the ACA Medicaid expansion enhanced match charge per unit. For those states that aggrandize, the federal authorities volition pay 100 percent of Medicaid costs of those newly eligible from 2014 to 2016.1 The federal share gradually phases downwardly to 90 percent in 2020 and remains at that level. In that location is no borderline to adopt the expansion; nonetheless, the federal match rates are tied to specific years.

- Disproportionate Share Hospital payments (DSH). DSH, or "disproportionate share" hospital payments are another source of financing available to hospitals that serve a large number of Medicaid and low-income uninsured patients; in many states, these DSH payments have been crucial to the financial stability of "safety internet" hospitals. Based on the assumption of increased coverage and therefore reduced uncompensated care costs nether the ACA, the law calls for an aggregate reduction in federal DSH allotments across all states, regardless of whether the state has expanded or not. These cuts have been delayed from FFY 2014 until FFY 2018 and are set to continue through 2025.ii

- State Financing of the Non-Federal Share. States have flexibility in determining the sources of funding for the non-federal share of Medicaid spending. The master source of funding for the non-federal share comes from country general fund appropriations. Over the past decade, states' use of other funds has increased slightly but steadily. This is likely tied at to the lowest degree in part to states' increased reliance on provider taxes and fees to finance the country share of Medicaid.

Implications of the Medicaid Financing Structure

- Role in Budgets. Medicaid plays a role in both state and federal budgets. While Medicaid is the third largest domestic plan in the federal budget following Medicare and Social Security, the program plays a unique role in state budgets. As a result of the joint financing structure, Medicaid acts equally both an expenditure and the largest source of federal acquirement in state budgets. Unlike at the federal level, states are required to regularly balance their budgets, making decisions about spending across programs as well every bit how much acquirement to collect. Balancing these competing priorities creates an ever present tension. Unlike other programs, land spending on Medicaid brings in federal revenues due to its financing structure. The implementation of the major ACA coverage expansions in 2014 led to higher enrollment and full overall spending growth in Medicaid; however, with total federal financing of the expansion, land Medicaid spending grew at a slower pace. Early evidence from states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion too indicates there are state budget savings both inside Medicaid budgets and exterior of Medicaid.

- Responsiveness to State Choices and Changing Needs. The financing structure guarantees states federal matching dollars for qualifying expenditures, assuasive federal funds to flow to states based on actual costs and needs. If medical costs ascension, more individuals enroll due to an economic downturn or at that place is an epidemic (such as HIV/AIDS) or a natural disaster (such equally Hurricane Katrina), Medicaid can respond and federal payments automatically adjust to reverberate the added costs of the program.

- Result of the Economy on Medicaid Spending. Medicaid is a countercyclical program. During economic downturns, individuals lose jobs, incomes decline and more people qualify and enroll in Medicaid which increases program spending at the aforementioned time every bit state revenues decline, making it hard for states to match ascension expenditures. Every bit economical atmospheric condition improve, spending growth in the programs slows. Congress has acted twice to temporarily increment the federal match during acute economic downturns, about recently during the Corking Recession.

- Effect of Medicaid Spending on State Economies. The influx of federal dollars from the fashion the Medicaid programme is financed has positive effects for land economies. The infusion of federal dollars into the state's economy results in a multiplier event, directly affecting not only the providers who received Medicaid payments for the services they provide to beneficiaries, just indirectly affecting other businesses and industries as well. The multiplier effect Medicaid spending has on land economies is expected to grow in states that adopt the Medicaid expansion. With the expansion's enhanced 100% match rate phasing downward to 90% in 2020 and remaining in that location thereafter, a new surge of federal funds not otherwise available will menstruation into states with comparatively modest add-on land full general fund costs. Early on experience in Kentucky showed both net fiscal benefits for the state driven by increases in land and local tax revenues too as job growth from the expansion.

How is Medicaid financed?

Federal Medical Assistance Match Rates (FMAPs)

Standard match rate. The basis of the state and federal partnership is governed by the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP.) Nether this financing arrangement, the federal government guarantees federal friction match funds to states for qualifying Medicaid expenditures (payments states brand for covered Medicaid services provided by qualified providers to eligible Medicaid enrollees.) The FMAP is calculated annually using a formula set along in the Social Security Act which is based on a country's average personal income relative to the national average; states with lower average personal incomes have higher FMAPs.

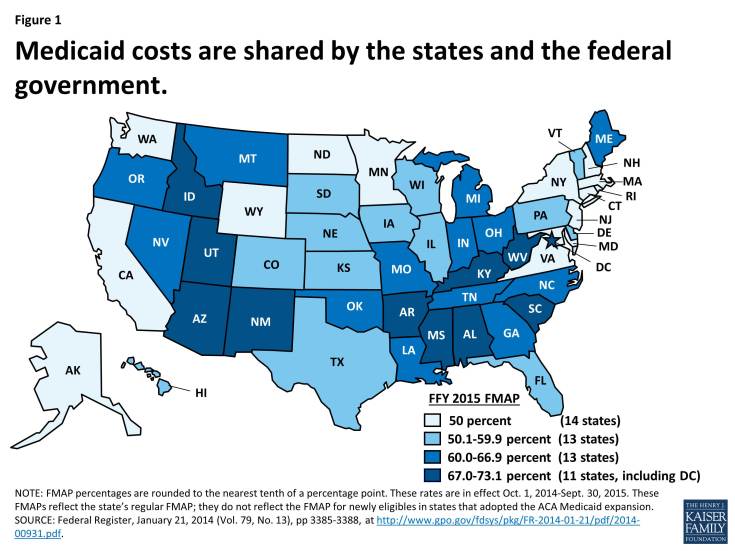

Personal income data are lagged, so data used for Federal Financial Twelvemonth (FFY) 2015 FMAPs are from 2010, 2011 and 2012. According to the statutory formula, for FFY 2015, the FMAP varies across states from a flooring of 50 pct to a loftier of 73.58 per centum. (Figure 1) This ways that every $1 of state spending on the program is matched with at least $one of federal funds; Mississippi, with the lowest per capita income level, gets $two.79 in federal funds for every $1 it spends on Medicaid.3

Figure 1: Medicaid costs are shared by the states and the federal government.

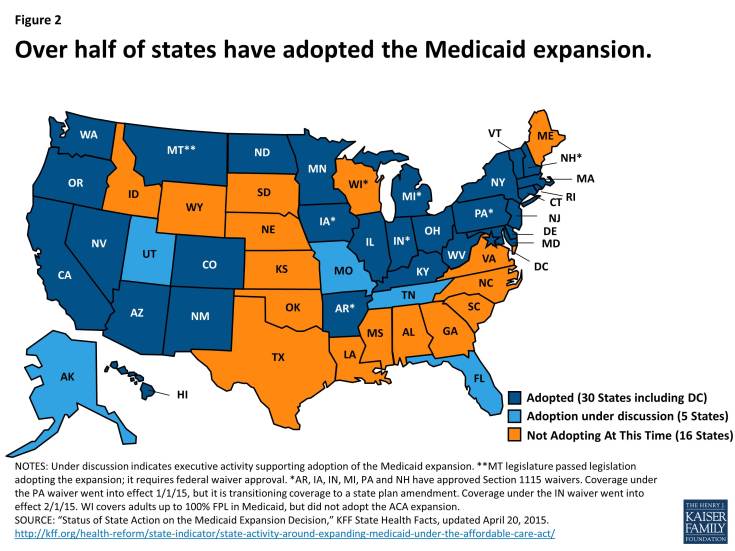

Enhanced match rates. While the standard FMAP continues to apply to the vast majority of Medicaid spending, there are a few exceptions that provide higher match rates for specific populations and services (these are summarized in Appendix Tabular array one.) Some of these higher match rates are long standing, such as the xc percent federal match charge per unit for family planning services and supplies that has been in result since 1973.4 Others were enacted in the ACA, the well-nigh notable of these beingness the enhanced friction match rate for those newly eligible under the ACA Medicaid expansion. As enacted, the ACA broadened Medicaid's role, making it the base for coverage of nearly all depression-income Americans with incomes up to 138 percent of poverty ($16,242 per yr for an private in 2015). However, the Supreme Court ruling on the ACA finer made the Medicaid expansion optional for states. For those that aggrandize, the federal government volition pay 100 percent of Medicaid costs of those newly eligible from 2014 to 2016.five The federal share gradually phases down to 90 percent in 2020 and remains at that level thereafter. The state's standard FMAP applies to services for those that were previously eligible for Medicaid. As of Apr 2015, thirty states (including DC) have adopted the Medicaid expansion, though debate continues in other states. (Effigy two) There is no deadline for states to aggrandize; yet, the federal match rates are tied to specific calendar years.

Figure 2: Over half of states accept adopted the Medicaid expansion.

Administrative match rate. Medicaid administrative costs in general correspond a relatively small portion of total Medicaid spending (5 percent or less.)vi In general, costs incurred past states in administering the Medicaid program are matched past the federal government at a fifty pct charge per unit. There are, however, some types of administrative functions which are matched at college rates.7 For example, as role of the ACA, states are required to simplify and modernize their enrollment processes, analogous eligibility and enrollment systems beyond Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program (Bit), and the Market, to facilitate enrollment and promote continuity of coverage. To assist states with these investments and organisation upgrades, federal regulations provided for an increase in the authoritative match rate – ninety pct federal funding for necessary investments in information technology, along with 75 percent federal match for operating expenses. The 90 percent match rate for initial eligibility-related IT investments was initially ready to elapse at the end of 2015, merely CMS recently released a proposal to extend the higher federal match rate permanently.eight

Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Payments

Another source of Medicaid financing focused on select hospitals is DSH payments. DSH, or "disproportionate share" hospitals are hospitals that serve a big number of Medicaid and low-income uninsured patients.ix In many states, DSH payments accept been crucial to the financial stability of "safety internet" hospitals. Federal DSH payments totaled $16.4 billion in FFY 2013.10 While states accept considerable discretion in determining the amount of DSH payments to each DSH infirmary, their discretion is bounded by two caps – i at the state level, and the other at the facility level. At the land level, the total corporeality of federal funds that each land can spend on DSH is specified in an almanac DSH allotment for each country. While there have been some special adjustments, the DSH allotments are by and large calculated based on the previous twelvemonth's allotment increased by inflation but and so subject to a cap of 12 percent of the total corporeality of Medicaid expenditures under the state plan that fiscal year. When the DSH caps were originally set, they locked in variation across states in DSH spending. At the facility level, Medicaid DSH payments are limited to 100 percent of the costs incurred for serving Medicaid and uninsured patients that accept non been compensated by Medicaid (Medicaid shortfall).

Based on the assumption of increased coverage and therefore reduced uncompensated care costs under the ACA, the police force calls for a reduction in federal DSH allotments. The statute required annual aggregate reductions in federal DSH funding from FFY 2014 through FFY 2020. However, recent federal legislation delays these reductions so that they would start in FFY 2018 and continuing through 2025.11 The legislation calls for aggregate reductions of $2 billion for FFY 2018, $3 billion for FFY 2019, $four billion for FFY 2020, $5 billion for FFY 2021, $six billion for FFY 2022, $7 billion for FFY 2023, and $8 billion for both FFYs 2024 and 2025. The methodology to distribute these amass reductions across states has not been determined; the ACA requires that the Secretary of HHS to take into account the post-obit in developing such a methodology:

- Impose a smaller percentage reduction on low DSH states;

- Impose larger percentage reductions on states that:

- accept the lowest percentages of uninsured people during the nearly recent year for which data is available;

- practise not target their DSH payments on hospitals with high volumes of Medicaid inpatients;

- practise not target their DSH payments on hospitals with high levels of uncompensated intendance;

- Have into account the extent to which the DSH resource allotment for a country was included in the upkeep neutrality calculation for a coverage expansion approved under section 1115 equally of July 31, 2009.

While the methodology has non been established to distribute these reductions at this fourth dimension, it is expected that the reductions are expected to occur across all states, regardless of the state Medicaid expansion decisions.

State Financing of the Non-Federal Share

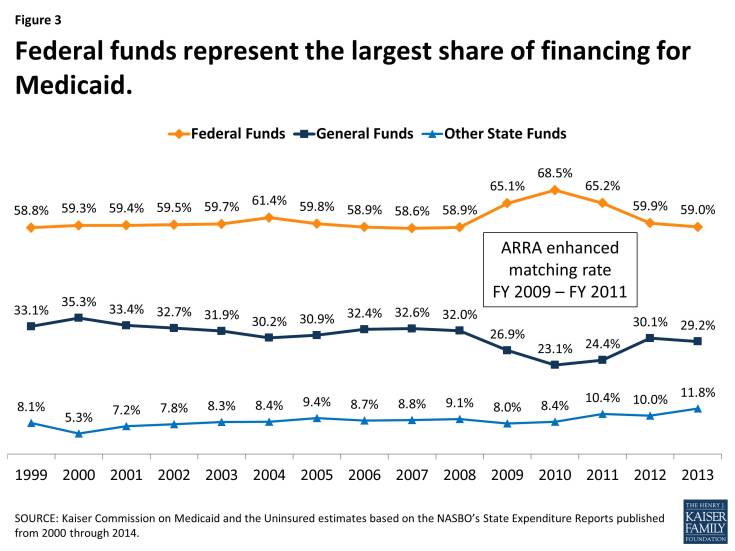

While federal funds have always represented the largest share of Medicaid financing (well-nigh $6 out of every $10 spent on the program), state and local funds also play an important part in financing the program's spending. States have flexibility in determining the sources of funding for the non-federal share of Medicaid spending – though federal law does require that at to the lowest degree 40 percent of the non-federal share comes from state funds.12 The master source of funding for the non-federal share comes from state full general fund appropriations. States also fund the non-federal share of Medicaid with "other land funds" which may include funding from local governments or acquirement collected from provider taxes and fees. Over the past decade, states' use of other funds has increased slightly but steadily. (Figure 3) This is likely tied to states' increased reliance on provider taxes and fees to finance the state share of Medicaid. Since state fiscal year (SFY) 2003, the number of states with at least ane provider taxation has increased from 21 to every state except Alaska in SFY 2014.13

Figure 3: Federal funds represent the largest share of financing for Medicaid.

While the Medicaid financing structure provides states with flexibility to design programs and run across changing needs, this structure also creates tension between the federal government and states nigh how financing should exist shared. Over the history of the plan states have used legal loopholes to maximize the amount of federal funds, sometimes through financing arrangements that may artificially inflate the FMAP. For example, in the 1990s and again a decade later, states were using DSH, provider taxes and then Upper Payment Limits (UPL – regulations on how much institutional providers can exist paid) to maximize federal revenues. In response, the federal regime passed a series of laws and rules to limit this spending and clamp down on inappropriate apply of federal funds. These practices have besides led some to advocate for a fixed resource allotment of federal funds to supplant the current open up-ended financing structure.

How the non-federal share of Medicaid spending is financed continues to be a focus of federal lawmakers. A recent report conducted by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) plant that while the majority of funding for the non-federal share of Medicaid spending does come from state general funds (more $half dozen out of every $ten dollars- well higher up the statutory requirements) the use of funds from local governments (commonly through certified public expenditures and intergovernmental transfers) as well as provider taxes and fees has increased in recent years. Given the increase in use of these funding sources, the GAO has called for increased data collection at the provider level to ensure compliance with current federal regulations.fourteen

Implications of the Medicaid Financing Structure

Touch on Budgets

Because of Medicaid's joint financing construction, the programme plays a part in both country and federal budgets. Medicaid plays a unique function in state budgets, acting as both an expenditure and the largest source of federal revenues to states.

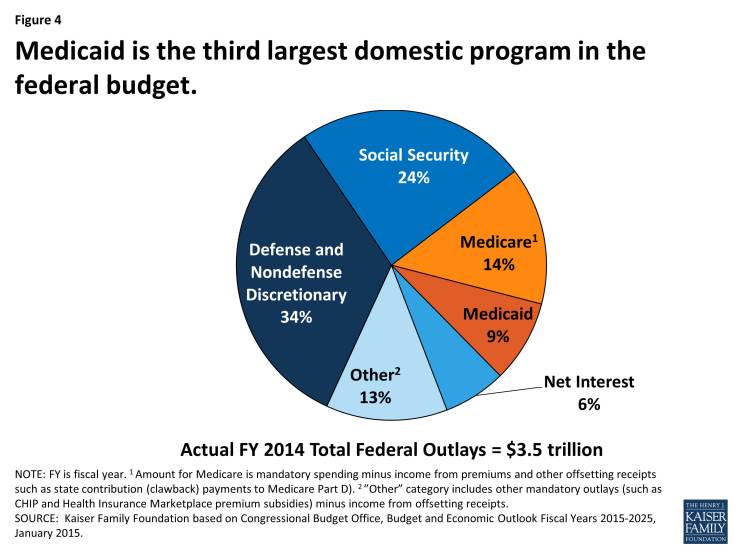

Medicaid is the tertiary largest domestic program in the federal upkeep following Medicare and Social Security. In FFY 2014, spending on Medicaid accounted for 9 per centum of federal spending. (Effigy four) The Congressional Upkeep Role projects federal Medicaid spending and plan enrollment to continue to grow over the coming decade due largely to the effects of the ACA changes such equally the Medicaid expansion. Much of the projected growth in enrollment and spending is driven by increases in the early years of this menstruum as states implement ACA changes, such as the Medicaid expansion.

Effigy 4: Medicaid is the third largest domestic program in the federal budget.

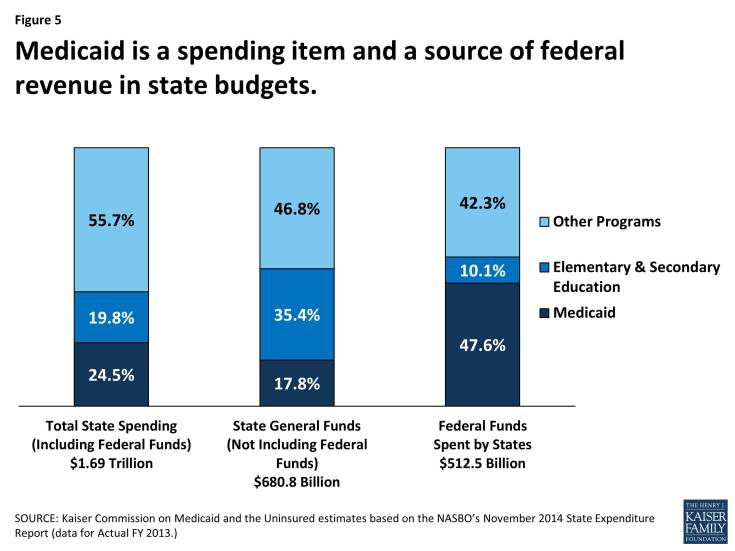

Medicaid is a spending and revenue particular in state budgets. Medicaid's role in state budgets is unique. Due to the articulation financing construction, states are guaranteed to receive at least $1 of federal funds for every $1 of state funds spent on the program. As a effect, Medicaid acts as both an expenditure and the largest source of federal revenue in state budgets. Medicaid is the largest source of federal funds spent by states; 48 percent of all federal funds spent by states come from the Medicaid plan. When looking at what states spend of their ain funds combined with these federal funds, Medicaid was the largest category of total spending across states in land fiscal year (SFY) 2013. The share of Medicaid spending from state sources, such as the land general fund, is smaller; in SFY 2013, Medicaid represented less than 18 percentage of state general fund spending, a far second to general fund spending for K-12 teaching (35.4%.) (Figure 5) The shares of general fund spending for Medicaid and K-12 education accept remained adequately constant over the past decade, though the share of full general fund spending on Medicaid did increase slightly as the temporary federal increase in friction match rates enacted under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Deed (ARRA) expired in 2011.

Figure 5: Medicaid is a spending item and a source of federal revenue in country budgets.

States generally are required to remainder budgets, creating tension across programs. Unlike at the federal level, states are required to balance their budgets. State lawmakers must therefore balance competing spending priorities (Grand-12 education, Medicaid, transportation, etc.) likewise as make decisions about the amount of revenue to collect. Balancing these competing priorities creates an ever nowadays tension. Increases in Medicaid spending are driven largely by enrollment growth simply also reflect states demand to respond to rising wellness care costs. While ever present, the ever present tension of balancing spending beyond programs is especially acute during economic downturns, when state revenues decline and Medicaid enrollment increases every bit people lose jobs and income at the same time every bit demand for other programs increases. Although the guaranteed federal friction match reduces the need for increased Medicaid spending from state sources, states still must increase the amount of non-federal dollars spent on the program in order to access those federal funds. States sometimes plough to provider tax revenues, inter-governmental transfers and other non-federal revenue sources to assistance fund the land share of Medicaid spending during such periods.

The implementation of the major ACA coverage expansions in 2014 led to college enrollment and total overall spending growth in Medicaid; all the same, with total federal financing of the expansion, land Medicaid spending grew at a slower footstep. The implementation of the major ACA coverage expansions in 2014 led to increased Medicaid enrollment among those previously eligible who are covered at the state'due south regular matching rate and among those newly eligible covered at the enhanced match rate in states that adopted the Medicaid expansion. While total spending on the program increased on average across all states at rates similar to enrollment increases, state spending on the program grew more slowly. This was due to the increased federal funds from the expansion leading expansion states to come across much a slower growth charge per unit for state spending on average compared to the charge per unit of growth for full spending (country and federal combined) or enrollment. This was in dissimilarity to historical patterns and to the experience in non-expansion states during this period where growth rates for state spending, full spending and enrollment are like.15

Early prove from states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion indicates in that location are state upkeep savings both within Medicaid budgets and exterior of Medicaid. Savings from within Medicaid programs include the transition of populations served through optional eligibility pathways, such as express do good waivers, medically needy spend-downward populations, Chest and Cervical Cancer Treatment plan enrollees among other groups, previously matched at the standard match rate. Afterwards adopting the expansion, these Medicaid enrollees could qualify for coverage under the newly eligible adult group, where their Medicaid expenditures are matched at the higher ACA expansion match rate. Early prove from some expansion states also indicates budget savings from either the reduced need for or the replacement of state spending on programs for behavioral health, corrections, public health and uncompensated care because of the federal funds for increased coverage in the expansion; some of these savings were captured equally reductions in state full general fund spending while others were reinvested, often to compensate for prior cuts in funding.sixteen

Responsiveness to Country Choices and changing needs

Medicaid spending responds to changing needs. The Medicaid financing model, which has remained largely unchanged since Medicaid was enacted,17 is unique beyond country and federal programs. Medicaid's financing structure guarantees states federal matching dollars for qualifying expenditures, allowing federal funds to flow to states based on actual costs and needs. If medical costs rising, more than individuals enroll due to an economical downturn or there is an epidemic (such as HIV/AIDS) or a natural disaster (such every bit Hurricane Katrina), Medicaid can respond and federal payments automatically adjust to reverberate the added costs of the program. During acute economic downturns, the structure allows increased federal funds to flow quickly to states by increasing the federal friction match to stimulate economic recovery and assist states struggling with declining revenue and increased enrollment and demand for assistance due to the economic downturn.

Medicaid financing supports state choice. This structure also underpins state policy choices most how to construction their Medicaid programs. Federal law specifies core requirements, such as mandatory benefits and mandatory groups that must be covered as a status of receiving federal Medicaid funding. However, beyond the core requirements, states have broad flexibility regarding optional eligibility groups, optional benefits, provider payment, delivery systems, and other aspects of their programs. This enables states to provide services and coverage suited to their state, but likewise means Medicaid coverage varies across the country.

This open up-concluded financing construction provides spending flexibility but makes federal outlays less predictable and driven past state spending decisions. To control federal spending, over the years some policymakers accept called for restructuring the financing arrangement to cap federal spending by cake granting federal spending or imposing other limits. Block grants generally provide fixed federal allotments to states that are based on electric current expenditures trended forward using a pre-adamant growth rate. The implications of whatsoever block grant or cap would depend on funding levels, inflation adjustments and many other details. Nonetheless, analysis of past proposals has showed that these changes could result in substantial shifts in costs to states, beneficiaries or providers or reductions in coverage or benefits if, to reduce federal spending, Medicaid funding is fix below expected levels.xviii Pre-determined levels of funding would make the program less responsive to irresolute programme needs, such equally when demand increases during economic downturns, epidemics or natural emergencies. Experiences from other federal programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) that operate under a block grant structure have shown challenges in setting and maintaining funding levels to encounter program needs beyond states and across fourth dimension.xix

Effect of the Economy on Medicaid Spending

The economy has a strong upshot on Medicaid enrollment and therefore spending. Medicaid spending and enrollment are affected by a number of factors – health care inflation, policy changes, etc. However, ane of the largest drivers of Medicaid spending and enrollment trends is changes in economic conditions. Medicaid is a countercyclical plan. During economic downturns, individuals lose jobs, incomes refuse and more people authorize and enroll in Medicaid which increases program spending. As economic atmospheric condition improve, Medicaid enrollment and spending growth tend to irksome.

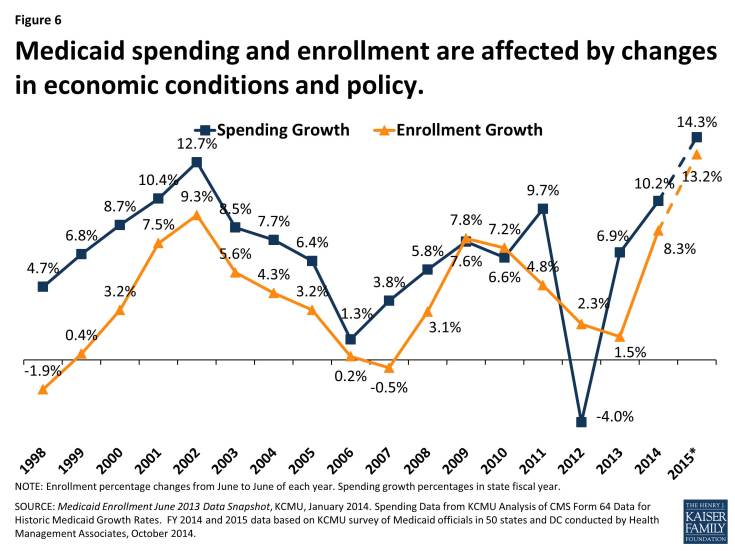

Over the past 15 years, Medicaid enrollment increased essentially during two major recessions, with annual growth peaking in SFY 2001 at over nine percent, and again at nearly 8 percent in SFY 2009. (Figure 6) While economical downturns increase demand for these program, they besides negatively affect state tax revenues. This places boosted pressure on state budgets as need for other forms of assistance (i.e. food stamps and unemployment benefits) as well increases. During economic downturns, states face up difficulty balancing these pressures and affording their share of Medicaid spending increases. In response, Congress has twice passed temporary increases to the FMAP rates to aid support states during specially acute economic downturns, virtually recently in 2009 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Human action (ARRA.) The about significant source of fiscal relief to states in ARRA was the temporary increment in the federal share of Medicaid costs. The ARRA-enhanced friction match rates provided states with over $100 billion in boosted federal funds over xi quarters, ending in June 2011.twenty

With the economy standing to improve, Medicaid enrollment growth across the country slowed considerably in SFY 2012 and SFY 2013. Over those two years, average spending also slowed, only the end of the ARRA enhanced match rates at the stop of SFY 2011 shifted state spending patterns as states tried to mitigate the loss of federal dollars in SFY 2012 resulting in a dip in spending in SFY 2012. With economic conditions improving, the largest commuter of Medicaid enrollment and spending growth during SFYs 2014 and 2015 has been related to the implementation of the ACA. 21 (Figure vi)

Effigy half-dozen: Medicaid spending and enrollment are affected by changes in economic weather and policy.

Medicaid Spending'due south Effect on Land Economies

The influx of federal dollars from Medicaid spending has positive effects for state economies. 22 Medicaid spending flows through a country'southward economic system and tin can generate impacts greater than the original spending alone. The infusion of federal dollars into the country's economy results in a multiplier effect, straight affecting non only the providers who received Medicaid payments for the services they provide to beneficiaries, just indirectly affecting other businesses and industries as well. For example, a medical supply firm may exist affected through its business organisation dealings with Medicaid providers — increases in Medicaid funding may affect a Medicaid provider's supply guild, which then may impact the medical supplier's purchases from its vendors and and so on. Both the direct and indirect furnishings induce changes in household consumption and tax drove primarily due to household income fluctuations. Employees of Medicaid health care providers that are directly afflicted or the employees of businesses that are indirectly afflicted may change their spending patterns according to increases or decreases in income — the change in income triggers the household to increase or subtract spending on consumer appurtenances. Due to changes in personal income and, subsequent spending, sources of state government acquirement — including income and sales taxes — would exist affected also.

Similar to previous findings, a review of economic analyses of the Medicaid expansion show that new funds as a effect of the Medicaid expansion are anticipated to accept a noticeable and sustained increment in state economic activity. Since the federal government fully pays for the cost of coverage for newly eligible beneficiaries for the first three years, a new surge of federal funds not otherwise available volition period into states with relatively little additional state costs. A December 2013 study found that the amount of federal funds estimated to come into states past 2022 if they decided to expand volition be substantially higher (one.35 times higher on average) than the amount of federal funds estimated to period into states through the federal highway program.23 A review of studies estimating the affect of the Medicaid expansion on state economies found that, regardless of the economic impact model used, all of the studies anticipated positive increases to state output and Gross Land Product (GSP). The magnitude of the impact depends on the level of current and anticipated new Medicaid funding and the economic conditions within the country.24 Early experience in Kentucky has shown both internet financial benefit for the land driven by increases in country and local tax revenues and job growth from the expansion.25

Decision

The Medicaid program is jointly financed by the federal and state governments with contributions governed past the FMAP formula that has remained largely unchanged over the program's fifty yr history. The federal/state matching organization provides a financing structure that is responsive to changes in enrollment and program needs, enabling states to adjust program expenditures in response to economic and policy changes. A program every bit big as Medicaid will always be a focus of upkeep scrutiny at the state and federal levels. Changes to Medicaid'due south financing structure would have implications for states, the federal government and beneficiaries which would warrant careful analysis.

Source: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-financing-how-does-it-work-and-what-are-the-implications/

Posted by: yonyoublicut.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Of The Following Services Must A State Offer In Order To Receive Federal Matching Funds?"

Post a Comment